Leisure & Culture #36

Death in the 21st Century: The Future of a Digital Graveyard

Digital Graveyard

Written by RMM

Photos by Tobias van Schneider // Shubert Ciencia// SafeBeyond // Yahoo Ending © Yahoo // Facebook Memorial Page © Facebook // Eterni.me

Photo Credit: Tobias van Schneider

In the end, everyone is dead. Less than a hundred years ago, our deaths were permanent — at most, our memories of the deceased lived on in photographs printed on Kodak paper, hand-signed letters hidden in envelopes or hazy Super-8 films. We could move on and occasionally look back on the past in these moments frozen in time.

These days however, our deaths have become complicated. Our lives have become entwined with the online world, ensuring that our memories live on – almost forever (or at least until the last servers die out).

Almost everyone these days will leave behind a data legacy that spans across social media which can help with mourning in the event of a death. So how can creatives and designers bridge the very fragile and human experience of mourning, with the uncanny digital environment that now holds everyone’s memories?

Photo Credit: Tobias van Schneider

First, let’s think about the visual language of death. What comes to mind? Sombre colours that channel solemnity or respect, soft shapes that help to ease emotion over time, static and solid objects that echo the way how the bereaved and deceased cannot move past the past.

A traditional Japanese Buddhist Altar. Photo Credit: Shubert Ciencia

So when things go online – when death goes online – things get a little strange. Things get a lot more personal. Which is not what you expect when you think about the internet (an amorphous, inhuman, network of bits and bytes). While memories used to live in our heads and hearts, they are now re-animated, looping endlessly in a fractured digital limbo. In social media, mourning happens simultaneously on multiple platforms. There is no ‘singular space’ to mourn someone’s death because all the pieces of our digital lives remain even after we die. In addition to a physical, private grave for solemn mourning, there’s also an immensely public digital grave for acquaintance to pay their respects. Therein lies a problem: how do we reconcile our offline and online selves after we’ve passed?

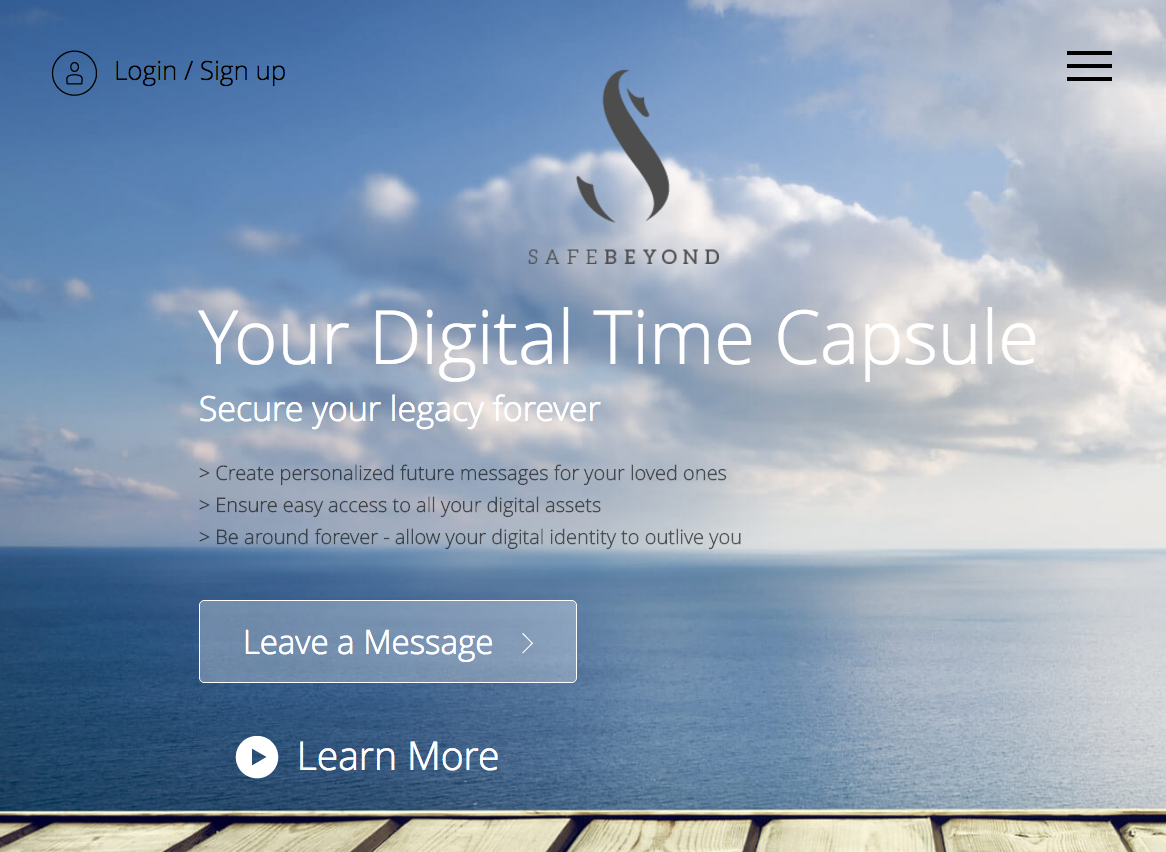

Photo Credit: SafeBeyond

Services like SafeBeyond, Eterni.me, Yahoo’s Ending, Google’s Inactive Account Manager and even Facebook’s Memorial pages have eschewed the typical visual language of death as mentioned above, instead opting for clean-cut, friendly sans-serif fonts and strangely enough, lots of blue. Images used are never gloomy or morose, think bright, evocative stock photography with vibrant or soothing colours and a multi-racial cast.

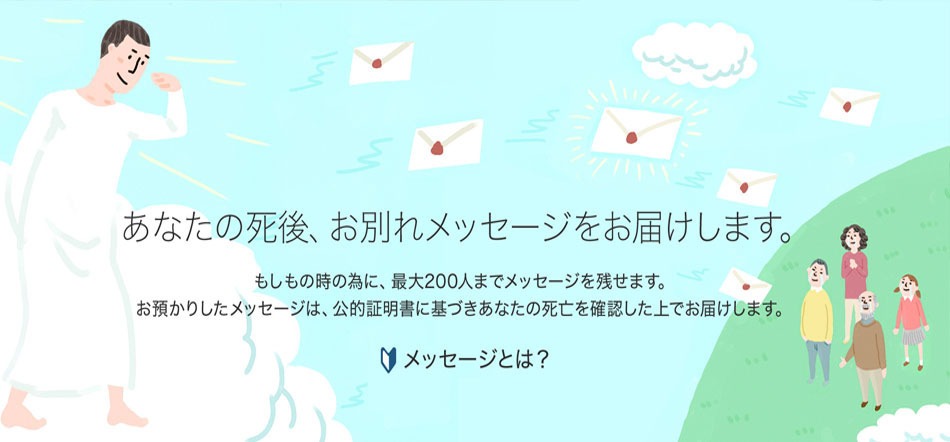

Photo Credit: Yahoo Ending © Yahoo

For the curious, here’s how sites like SafeBeyond work: you upload written and video wishes to your loved ones; these wishes are kept private until you pass away or are released at a specified time — kind of like a legacy time-capsule. Yahoo Ending’s time-capsule service has ended this year, but it still acts as a coordinator between you and local funeral companies to help you plan your journey to the afterlife.

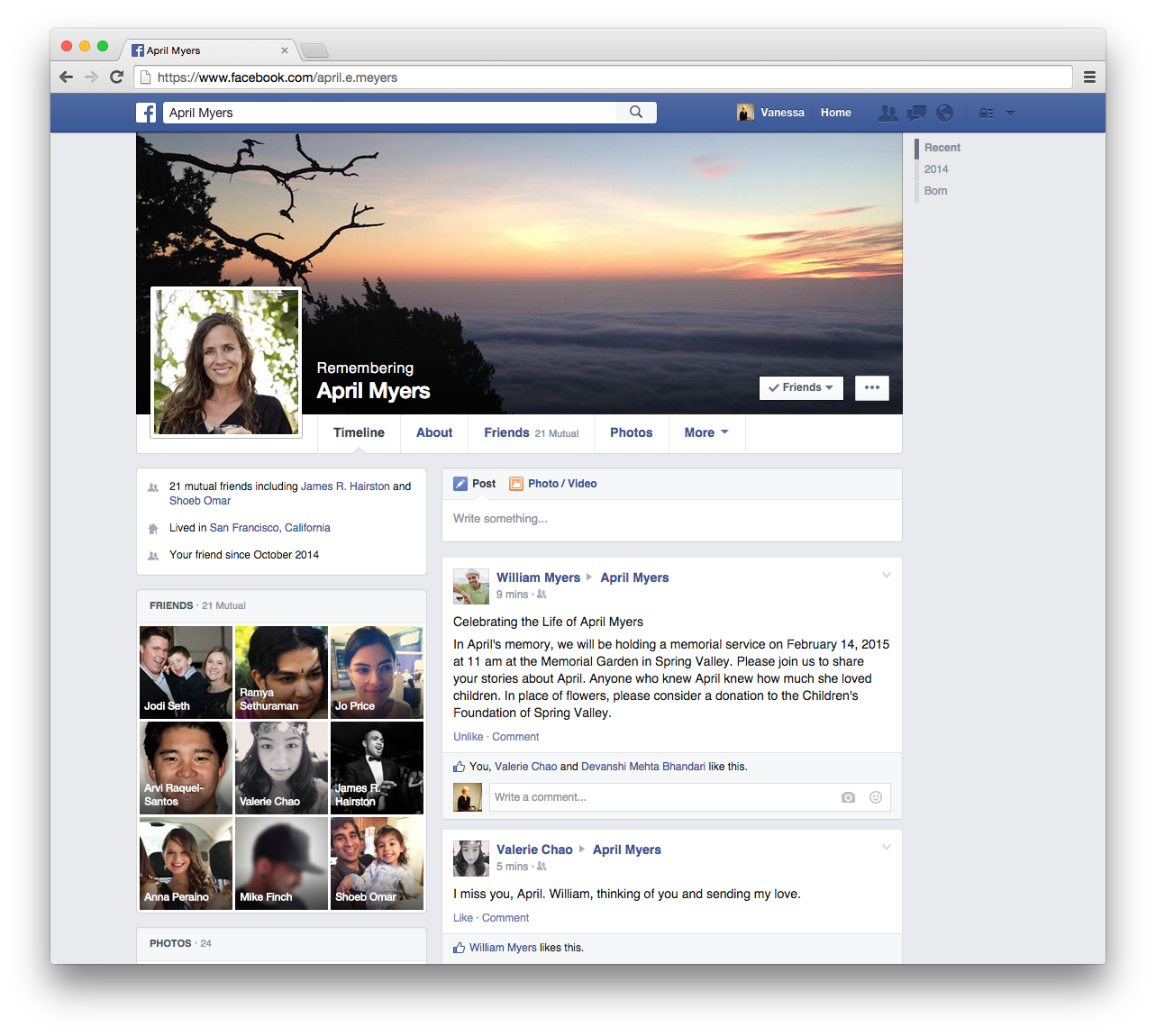

Photo Credit: Facebook Memorial Page © Facebook

ocial media conglomerates like Facebook and Google have taken it on themselves to provide a means to an end for your online lives. They’ve designed a seemingly seamless transition from life to afterlife that allows for an expansion to our normal mourning practices: instead of tombstones and plaques, we have web memorials. Instead of notarized wills, we have digital ‘legacy executors’. While well-intentioned, there’s virtually no consensus on a user interface that helps with mourning and make it less complex and confusing to the bereaved.

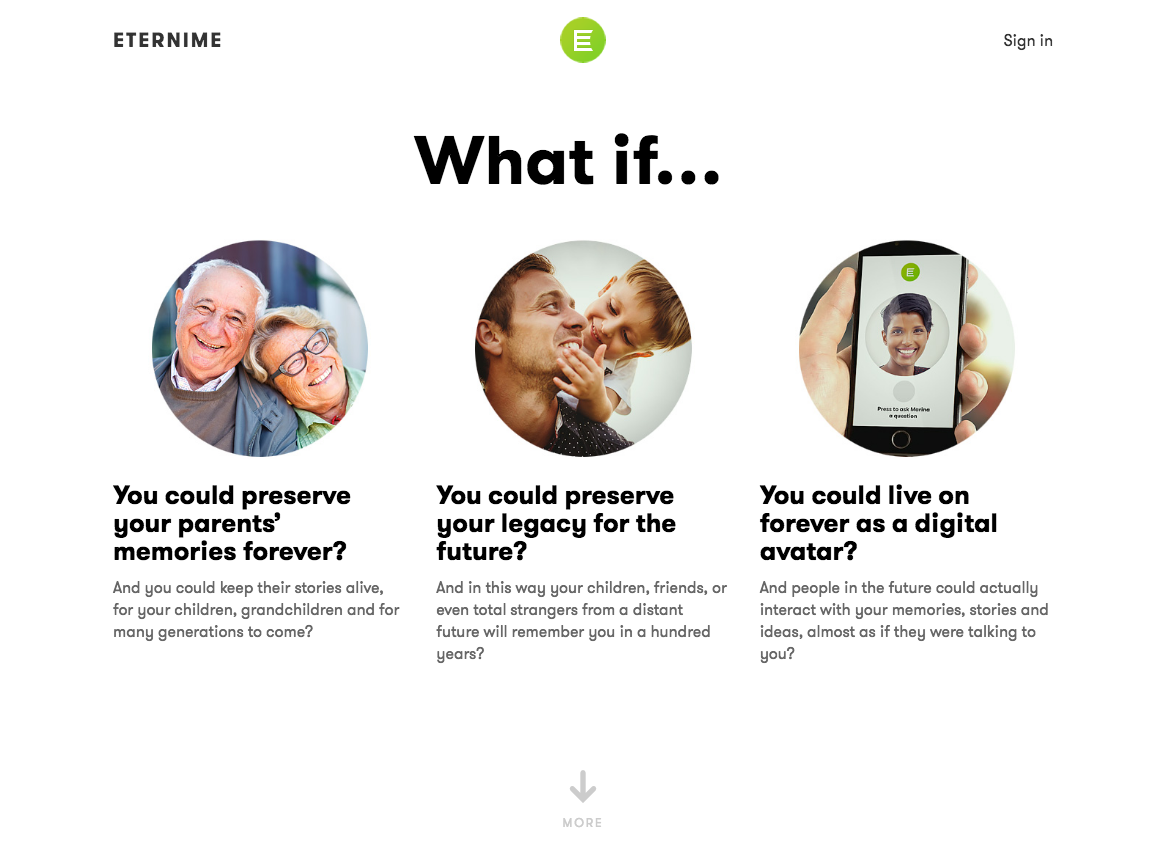

Eterni.me’s Friendly Interface. It still has yet to launch. Photo Credit: Eterni.me

And then there’s Eterni.me, which bears an uncanny resemblance to an episode off Charlie Brooker’s speculative sci-fi series Black Mirror. Using data from Facebook, Twitter, e-mails, photos and whatever you deem fit to supply it, you can curate a version of your life to bequeath your descendants upon your death.

It doesn’t stop there. Like the service in in ‘Be Right Back’ (that episode in the aforementioned Black Mirror), Eterni.me has a unique feature which is essentially a Siri-version of you: a 3-D avatar that has your personality and learns to sound more like you the more you “train” it to adopt your vocabulary and sentence patterns. The difference between ‘Be Right Back’ and Eterni.me is that the latter doesn’t try to replace the deceased, instead opting to be a librarian of sorts, doling out information to your friends and family.

What Eterni.me promises, even in its benign librarian form, hints at a much more complicated future with the digital graveyard. Some of us will never be content with interacting with a memorial page, speaking into a void that never responds. Others, like Eugenia Kudya (Founder of Luka, an Artificial Intelligence start-up), will rage against the dying light and build magical and monstrous manifestations of the afterlife, refusing to let the dead stay dead. In a nutshell, Kudya, devastated by the untimely death of her best friend Roman Mazurenko, decided to create a bot that spoke just like her late friend. The Black Mirror brought to life.

As creatives, designers and people firmly entrenched online, we need to find a balance between digital recollection and emotional release.Start-ups hoping to cash-in on this inevitable phenomenon need to find what is sustainable and what is empathetic for both the deceased and the bereaved — because grief, after all, affects us all.